Martha Wells got her start writing Godzilla fan-fiction as a small child, creating enormous, detailed maps of Monster Island on typing paper. After spending her college years writing and attending workshops like Turkey City, she made her first sale in 1993, when Tor Books accepted her novel, The Element of Fire. Over the course of a twenty-five-year career, Wells has jumped between high fantasy in the Raksura series, court intrigue and magical knavery in her Ile-Rien books, and far-future tech conspiracy in the Murderbot Diaries. She’s written Star Wars tie-ins, and expanded the world of Magic: The Gathering, as well as writing wonderful YA and two innovative, highly original stand alone fantasy novels for adults.

Whether you like snarky droids or intricate magic, whether you prefer sprawling series or self-contained stories—Martha Wells has written something that belongs on your bookshelf. But when you go a little deeper in Wells’ work, you’ll notice one shining cord that runs through each story: unexpected protagonists.

Wells was the toastmaster of 2017’s World Fantasy Con, where her speech “Unbury the Future” was met with a rapturous response. You can (and should) read the whole thing, but the spark notes version is this: SFF, and pulps, and comics, and scientific breakthrough have all, always, been created by an extraordinarily diverse group of people, who should all be represented by our culture. As you’ll see, her own work bears this idea out beautifully. She often circles around issues of identity. How do we know who we are? How are we formed by our environments, our opportunities, other people’s perceptions of us? She also build unique class structures and social hierarchies into every world, exposing her characters’ prejudices as their plots unfold, and prodding at the assumptions that create divisions among people (and Murderbots) in ways that build into the action of the books, rather than stopping to pontificate. As she told ScifiFantasyNetwork, “I usually start developing the characters when I know the kind of story I want to tell. The world building also plays a huge part. The world the book is set in determines everything about the characters, their physical abilities, their personalities, their problems and goals. The Story is determined by the world and the characters. They’re so intertwined I find it hard to talk about them as separate things.”

She highlights points of view that are seldom heard from, as evidenced by the protagonists of The Death of the Necromancer and Wheel of the Infinite respectively: “Those two were deliberate choices. For Nicholas, I wanted to write a protagonist who in most books like this would be the antagonist, if not the outright villain. For Maskelle I wanted to write about an older woman protagonist because I’d been thinking a lot about the portrayals of older women in books and movies around that time.” In the Raksura series, Wells built gender identity into the world by setting the stories in a matriarchal culture in which most people are bisexual, and working through the romantic entanglements and family structures that would result in that society. In City of Bones our main character is another hybrid, like Murderbot, who is considered low-class and unworthy of basic rights. In her Emilie books, Wells gives us a “girl’s own adventure” to match any boy’s. Again and again, Wells makes sure to tell the stories of the oppressed, the overlooked, the underdog.

The Murderbot Diaries

I could have become a mass murder after I hacked my governor module, but then I realized I could access the combined feed of entertainment channels carried on the company satellites. It had been well over 35,000 hours or so since then, with still not much murdering, but probably, I don’t know, a little under 35,000 hours of movies, serials, books, plays, and music consumed. As a heartless killing machine, I was a terrible failure. I was also still doing my job, on a new contract, and hoping Dr. Volescu and Dr. Bharadwaj finished their survey soon so we could get back to the habitat and I could watch episode 397 of Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon.

Thus begins Wells’ The Murderbot Diaries, the story of a SecUnit—a security droid made of a hybrid of organic parts and tech—who has gained sentience and hacked its own surveillance software in order to learn who it is. For now, it calls itself “Murderbot.” Of course the hack has to be an absolute secret, since Murderbot’s corner-cutting, not-entirely-trustworthy parent company will strip it for parts if they learn the truth. But keeping secrets becomes much more difficult when an accident at a survey site require Murderbot to save one of its human clients, revealing much more personality than anyone was expecting. And when that accident turns out to be sabotage, Murderbot finds itself having to go on a rescue mission for a bunch of people it doesn’t even like, all while pretending to be an obedient, unthinking drone.

The series begins with comedy, but quickly becomes a moving meditation on consciousness, autonomy, privacy…all Murderbot wants to do is keep to itself and, think, and allow its personality to form on its own terms. Instead, again and again, it must deal with humans who make assumptions about its intelligence and character, assuming that it’s either more human or more machine that in is, and never allowing for the ambiguity they would in a fully biological human. The books also unfold over a varied world of mining planets and space travel, each novel featuring a diverse cast of scientists. Plus, since Murderbot is a human/robot hybrid, gender is pretty irrelevant to it, which leads to interesting moments of humans attempting to put their own ideas and prejudices on it.

Wells also reveled in the novella format. Speaking to The Verge, she said, “It let me build the world in small, hopefully vivid segments, and left a lot of scope for my imagination as well as the reader’s. You can do stories that mostly stand alone and only refer briefly to the overall arc, and explore a lot more of the world.” The first Murderbot book, All Systems Red was a 2017 Philip K. Dick Award nominee, a 2017 Nebula Award Finalist, and an Alex Award winner. Three more diaries are coming in 2018—Artificial Condition in May, Rogue Protocol in August, and Exit Strategy in October—so you can have an entire year of murder!

The Raksura Series

The seven books of Raksura series—five novels and two volumes of Stories of the Raksura (each of which contain two novellas)—follow Moon on his journey from terrified outcast to powerful leader. In Book One, The Cloud Roads, Moon is the only shape-shifter among the tribes of the river valley. He has no memory of his birth parents, but knows that he must hide his identity in order to be accepted by his adopted home. Inevitably, his identity is discovered, but in a stroke of fortune he meets another shape-shifter like himself, and is able to escape to a new life…one with its own complications.

Moon soon finds himself among the Indigo Court of the Raksura, a wide-ranging family of shape-shifters, and for the first time, knows that he belongs. He even becomes consort to the sister queen Jade, a position of high honor in the Indigo Court. But no sooner has he begun his new life than more worries arise: blight at the heart of the Court’s central tree, rival Courts bent on war, and mysteries surrounding Moon’s own origin. Throughout the series Wells shows us facets of a gorgeous, complex world, informing a story of one character’s desire to find a true home. She explores the gender politics through Moon’s story—as one of the few fertile males of the Raksura, he’s expected to be Jade’s consort to provide her with children, which gives him a certain status but also means that his life is lived in Jade’s service. As bisexuality is the default orientation of the Raksura, certain assumptions that are made in other fantasy worlds are completely up-ended here.

The World of Ile-Rien

The five novels of Ile-Rien have wonderful characters, action, and intrigue, but an even more interesting aspect is that you’re really reading about the life of a kingdom. Readers first travel to Ile-Rien in The Element of Fire, which begins during the reign of the Dowager Queen Ravenna of the Fontainon dynasty. The country’s technology and arts make it roughly equivalent to Baroque-era France, with the notable exception that when a person travels to the university city of Lodun they’re as likely to meet a student of sorcery as one of law or medicine. Queen Ravenna rules from the opulent capital city of Vienne, joined by her son, King Roland and his young Queen, Falaise. She also has a tense relationship with her deceased consort’s illegitimate daughter, the Princess Katherine, who practices sorcery under the (awesome) name ‘Kade Carrion.’ When treachery threatens the kingdom, Thomas Boniface, Captain of the Queen’s Guard (and Ravenna’s former lover) must ferret it out, no matter how high the corruption goes, or how much magic must be made.

The second book, The Death of the Necromancer (a 1998 Nebula Award Finalist!), jumps ahead in time, and finds one of King Roland’s descendants ruling over a gaslit city as Nicholas Valiarde, the most cunning thief in the kingdom, plots his revenge on Count Montesqu, the noble who wrongfully sentenced his grandfather to death. But when his plan is interrupted by eerie, inexplicable event, Nicholas realizes he must enter a brutal magical battle…and there’s no guarantee he’ll make it out alive. The final three books, The Wizard Hunters, The Ships of Air, and The Gate of Gods are collected as “The Fall of Ile-Rien Trilogy,” and bring Ile-Rien into a more modern era. A terrifying army known only as the Gardier attack the country without mercy, striking from black airships and surrounding the city of Lodun. Nicholas Valiarde’s daughter, the playwright Tremaine, embarks on a nearly impossible quest to stop the Gardier…or at least save whatever she can of Ile-Rien and its people.

Can a nation be a protagonist? While Wells chooses to focus on a series of female rulers, sorcerers, and adventurers (already an unusual storytelling decision) she also tells a story that spans centuries, ultimately making the kingdom itself more of a main character than any of the humans.

Standalone Novels: City of Bones and Wheel of the Infinite

Wells’ second novel, the 1995 fantasy City of Bones, draws on the Arabian Nights, steampunk, and post-apocalyptic tropes to create a desert world by turns captivating and oppressive. Charisat is the richest city of the Waste, where class distinctions and hierarchy are built into every thread of the fabric of life, and where the heat presses down inexorably on all. In Charisat the bio-engineered relics dealer Khat can scratch out a life that’s just shy of legal, working with a foreign, fully human, partner, and carefully dancing through transaction using tokens and barter—as no one at their class level is permitted money. But Khat’s precarious life starts to slip when he’s pushed into working with Elen, a Patrician Warder. The Warders are essentially a police force…with psychic powers that can cause insanity. Elen works for the Master Warder, Sonet Riathan, who believes that if Khat can get him some particular relics he will be grant more power than any Warder has yet achieved…but of course there’s a catch.

As Khat and Elen soon learn, the Relic is tied to horrifying supernatural force—the same force that ruined their world and created the Waste eons ago. And in handing these relics over to Riathan, there will be nothing standing between what’s left of the world and utter destruction.

City of Bones isn’t a typical “magical chosen one story.” Khat is often a distasteful protagonist, but he’s also an oppressed minority barely existing in a land that is so post-apocalypse that everyone’s just learned to live with it. He isn’t mentored by a wise elder, he’s thrown into a fractious partnership with a magical underling. But are they any less worthy of life and justice than the rarefied upper classes?

* * *

Wells’ 2000 fantasy Wheel of the Infinite gave us a rich fantasy world and a twisty magical conspiracy. Each year, in the Temple City of the Celestial Empire, powerful magic-users known as the Voices of the Ancestors convene to weave the Wheel of the Infinite. The Wheel may look like a pretty piece of sand art, but in truth it is the very crux of reality, as anything that is altered in the Wheel echoes out into life. As the end of a Hundredth Year approaches, a chaotic dark storm forms within the Wheel—every attempt to remove it fails. Finally, the Voices decide to summon Maskelle, an outcast of their order, to add her powerful magic to their own.

There are problems.

The Voice of the Adversary, the Voice Maskelle channels, was never human, and is regarded as a demon in other cultures, but has always been a voice for justice. How, then, did Maskelle’s final prophecy fail, leading to murder, chaos, and banishment? In the wake of this failure, Maskelle hasn’t used her power. She knows she will not be fully trusted upon her return to the Temple City, and has no way of knowing if the Voices will listen to her. Nevertheless, she heeds the call. She enlists the help of Rian, a cunning swordsman from another land, and soon comes to learn that the black storm tormenting the Wheel is even more powerful and malevolent than the Voices had feared. It will take all of her resources to save the Empire.

There’s one other problem: the Voice of the Adversary, the only one she can truly rely on in her battle with evil, may be insane.

Maskelle is an older woman, with a rocky past behind her, facing a lot of distrust from her former comrades. Her only ally is a foreigner—also not trustworthy—and her guiding Voice may be unhinged. Wells could have told her story from the point of view of an ingenue, or a trusted Voice, but instead comes at the tale from a spiky, difficult corner.

Young Adult Works

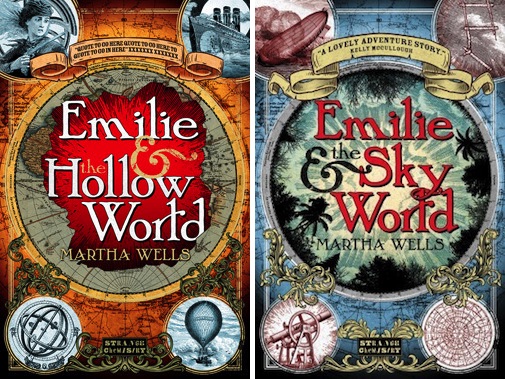

Emilie and the Hollow World is, as its title would suggest, a hollow world story. Emilie’s plan to run away from her tyrannical aunt and uncle goes wrong almost immediately when, overwhelmed by the chaos of the docks (and possibly a pirate attack) she has to flee The Merry Belle and instead board a mysterious ship on an otherworldly mission. Fortunately Lady Marlende, the mission’s leader, decides to take Emilie into her charge. She explains the reason for the ship’s voyage: a journey into the earth to search for her vanished father, Dr. Marlende. The trip beneath the waves and into the earth is daring enough, but when the ship is damaged on arrival the crew members begin to suspect sabotage. Only Emilie’s wits can help them return to the surface of their world.

Wells’ sequel, Emilie and the Sky World, follows the intrepid heroine to Silk Harbor (her original destination in her first outing) as she and a friend of Lady Marlende’s take an airship on a voyage into the beautiful-yet-treacherous world of the upper currents.

In her 2017 World Fantasy Con toast, Wells asserted that SFF has always been diverse, and the illusion that it isn’t is a work of revisionist history:

Secrets are about suppression, and history is often suppressed by violence, obscured by cultural appropriation, or deliberately destroyed or altered by colonization, in a lingering kind of cultural gaslighting. Wikipedia defines “secret history” as a revisionist interpretation of either fictional or real history which is claimed to have been deliberately suppressed, forgotten, or ignored by established scholars.

That’s what I think of when I hear the words “secret histories.” Histories kept intentionally secret and histories that were quietly allowed to fade away.

As Wells explains, we don’t talk about seminal filmmakers Oscar Micheaux or Ida Lupino because Hollywood didn’t want to celebrate Black or female directors. When people talk about the birth of rock’n’roll, they’re more likely to talk about Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis because the white Baby Boomer narrative put those men at the center, rather than honoring Sister Rosetta Tharpe. And unless you’re taught that many, many women and people of color wrote pulps and dime novels and comics and submitted stories to early SFF magazines, you’re left with the impression that it was all John Campbell and H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, following from the earlier works of H.G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne—you won’t know to add the names Pauline Hopkins, Charles W. Chesnutt, Mary Elizabeth Counselman, Orrin C. Evans, and a whole shelf full of other writers who haven’t gotten their due recognition.

It’s easy to think that “diversity in SFF” is a new thing if you’re not educated about the women and POC that have been creating SFF the entire time. Wells’ speech named many, many people who should be folk heroes to those of us who love these genres, an she provides resources to learn more about them—but many of them were nearly forgotten entirely. “Unbury the Future” holds a clear lens up to Well’s own career-long project: don’t just tell the story of the elite, the ruling class, the male, the able bodied. Tell everyone’s stories. In our genre anything is possible, and the stories we create should reflect everyone, and welcome everyone.